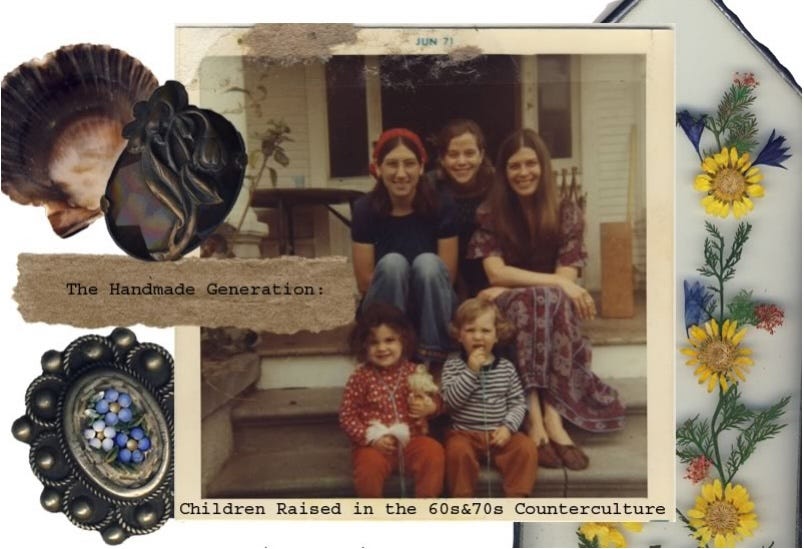

Introduction: Situating The Cultural Complex Within History

Section 2 of my book: Transmissions From Parents to Children Within The Counterculture

What Makes A Person Post-Cool?

There is very little written about the counterculture children of the 1960s and 70s. Academic work on the 1960s era is primarily focused on the adults of the counterculture, the parents of my defined Post-Cool group. A small subset of this academic work is about the parenting beliefs and practices of commune hippies, and one large longitudinal study, begun at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1974, studies counterculture families. This UCLA study called “The Family Lifestyles Project” continued for 20 years. The last article to appear pertaining to this study, was published in 1998 when the Post-Cool Kids were young adults, and at their parent’s mid-life. After this last paper there has been no follow up study of this cohort during their adult years.

Despite this limited academic identification a cohesive Post-Cool group can be identified. There is a recognizable type of American person, the counterculture-raised child, who has emerged in literature and film depictions in a variety of caricatures. Alternative films, documentaries, and mainstream Hollywood film and television all make it quite clear that the cultural traits of a person raised with counterculture values have developed into a recognizable Post-Cool Kid type. These traits are not only familiar to others within the counterculture, but are coherent enough that they can be recognized from outside of the counterculture as well. This demonstrated recognition by American society, either overtly or unconsciously, identifies these individual people brought up with counterculture values and lifestyles, as having consistent traits. In examining and attempting to define these traits as part of naming this Post-Cool group I examined content from a variety of sources. Included in this was an extensive look at popular culture images; memoirs; online groups; blogs; informal media shares; articles from online magazines; and original findings from one-on-one interviews. This large collection of original content provided a vast sample of direct experience narratives from individuals raised in various parts of the counterculture.

Marianne Dekoven writes that much of the study of the 1960s is divorced from the emotive experience that was felt at the time. Academic arguments range from the ultimate insignificance of the era to intense romantic nostalgia. What Dekoven claims is missing is a real assessment, a phenomenological awareness of the state of being in the experience of the sixties era, and the values that came out of those experiences that have been carried through life by the individuals involved. These studies of the era reflect the emotional state of the Baby Boomer Generation, who participated in the transformations of the era as young adults and into adulthood and now look back with nostalgia. The children raised in the counterculture can provide an all together different measuring stick for the impact sixties era transformations have had on United States’ culture. In order to understand the emotions and legacies of the 1960s it is necessary to examine the children that were born into the experience, lived through it, and who perhaps were most shaped by the ideas and experiments of their parents. Published memoirs about growing up in the counterculture have become increasingly more prevalent in the last two decades. These memoirs help flesh out the description of the experience of being in this culture. They also provide weight to my argument that the larger American culture has begun to recognize the existence of this subculture and have an interest in it.

These memoirs continue to grow in number. My favorites so far include: Wild Child: Girlhoods in the Counterculture edited by Chelsea Cain; Split: A Counterculture Childhood by Lisa Michaels; Notes From Nethers: Growing Up in a Sixties Commune by Sandra Eugster; Pagan Time: An American Childhood by Micah Perks.

The existing history of the sixties written by academics of the Sixties experience often examine the values that emerged from the era as if they were bugs trapped in amber. In our current time there is a need to move the story forward. The dominant perspective on The Sixties, that of the generation who “made it happen,” at this historical distance feels old and clichéd. As a result the issues and discourse of the time are labeled that way as well. They become a sarcastic joke along with depictions of old annoying hippies ranting out their story. Yet, the cultural energy generated by The Sixties era has not been extinguished. People are still drawn to the myth and the romantic revolutionary story of that time of change. This speaks to an undeniable psychological need for utopia, and the leaps of cultural change, and creative freedom it represents. Americans are particularly drawn to this utopian longing. The longing for utopia to be realized feeds into the romantic fantasies of The Sixties as a special and notable time. The stories developed within that cultural shift continue to emerge with new hippie variants, transformational festivals, discussions of sustainability, social justice movements, and even Van-Life MEMEs. The end of the Cold War, and the deconstruction of dialectical revolution creates a critical shift from universal notions of utopia to a limited personal and partial utopian style of progressiveness. Yet, utopia is still a piece of the American landscape at every turn, from Las Vegas, to Disneyland, to Burning Man.

Advocates for the idea of the sixties as transformational have in the past been criticized as romantic universalists. Much of the countercultures narrative got caught in essentialist arguments to the detriment of the underlying social and political critiques they espoused. The progressive humanism and activism that followed the era could also be attributed to other sorts of movements and world events: civil rights, economic changes, post-colonial movements, or in the case of the right wing, religious led volunteerism. Some critics argue that the sixties counterculture does not deserve the level of analysis that it has, or that the counterculture was the exception not the rule of the Boomer generation. The ideological transition from universal ideologies, still present in the Cold War, to personal acts as political expression, emergent in all of the movements of the Sixties era, were popularized and saturated into society through the colorful and outspoken counterculture. Each movement of the sixties existed within its own cultural discourse, but it is the post modern layering of all of these movements developing in the historical and cultural moment simultaneously and informed or reactive to each other that produced the radical shift in culture. I am taking then, a more complex historical approach to a periodization of the sixties phenomenon. Seeing the simultaneous cacophony of change, rather than a cohesive unified picture, as the historical system that informs the particularity of my topic. I am not saying that this segment of sixties culture is all that was happening, or even the primary activation for the changing culture. My goal is to collect a set of cultural items and actions, and explore it in such a way that nuances of both, sixties specific counterculture, and American utopianism arise out of the patterns, and inform a larger cultural conversation.

Fredric Jameson makes an argument for treating a good chunk of 1970s counterculture activity under the heading “60s Era.” His arguments are that those cultural attributes we identify as belonging to all things Sixties actually span into the 1970s. Jameson places the end date at 1974 setting a precedent for claiming a continuity between 1960s values and 1970s cultural attributes within the counterculture. I will extend this date to 1979 as the cultural attributes that I am identifying as Sixties adjacent include lifestyles and family structures that were still active and being pursued in their original large numbers until the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the Reagan Era.

There are many critics who dismiss the cultural revolution of the 1960s as a fiction or as a dangerous minority, especially the neo-conservatives who emerged out of the same era. These dismissive critics proclaim the 1960s as a finite phenomenon that failed. Yet, there is a life force to the 1960s counterculture. The dreams that emerged from the New Left culture continue to grow in the global imagination. There remains a style of change that can only be traced to the Youth Culture counterculture story. The impact of radical politics and the counterculture on political discourse, perceptions of identity, musical traditions, and culture never fades from view. The continued influence of sixties culture on the American psyche can be seen in the endless regurgitation of the subject in film and literature—as exemplified by films like director Ang Lee’s Taking Woodstock complete with psychedelic promotional posters—as well as the ubiquitous use of the term Boomer, by which writers and journalists often mean “the counterculture.” This group is used as a measurement for the values of every election and grass roots movement that is discussed in mainstream news presentations. Direct contact with the energy from this time has changed many human lives. The recognized value of phenomenological experience, that has begun to express itself in everything from medical diagnosis to academic theory, is a direct result of the 1960s counterculture’s valuation of pro-naturalism and authenticity, as is a looseness of emotional expression that can be witnessed in everything from therapy culture to negotiation strategies in child rearing. Though some dismiss the counterculture as simply “sex, drugs, and rock and roll,” freeing the inhibitions in a Dionysian ecstasy, there was at root political action in the lifestyle choices of the sixties counterculture. Theodore Roszak writing in 1968, describes the collective intention, “They seek to invent a cultural base for New Left politics, to discover new types of community, new family patterns, new sexual mores, new kinds of livelihood, new esthetic forms, new personal identities on the far side of power politics, the bourgeois home, and the consumer society” (66). The lifestyle choices were a cultural flowering that began with a social and political critique and break from the dominant culture.

The 1960s reframed cultural possibilities. The counterculture created new forms of tribalism outside of blood ties or institutions of belief. They experimented with ways of communicating and learning. They moved to communes like Gaskin's Farm. The Farm attempted to develop telepathy, among other things. Gaskin was a charismatic culture leader who gathered a large group of counterculture people and moved them from the streets of San Francisco to a large piece of land in Tennessee. They created new and different systems of working and living together as described in many commune related memoirs. They invented new ideas of parenting. The era was exciting. There was awareness that new ways of being in the world, and of being in community, could be invented. This excitement continues to be visible when the people that were present in it are asked to speak and remember the experience. Language, life, society, became living and changeable. These experiments not only impacted the adults who created them and the world who watched them do it, but also the children who were raised in it. Though many of these experimental social constructs were short lived, or as measured in the “Family Lifestyles Project” done through the University of California Los Angeles, were less distant from the conventional society than the counterculture had hoped, the initial impact did shape the worldview of the children. They then brought this experience with them from childhood into their adult lives, and the larger society.

The term counterculture as I am using it here connotes an expanded social grouping from that currently understood in the popularized idea of counterculture. The current popular culture definition conflates counterculture with hippie. In this study the word “counterculture” refers to those people of the sixties era who made up a wide range of experimental backgrounds, including hippies but also the new left, and new and experimental religions such as the Krishna Movement, or isolated creedal communes. There is a precedent for this. Theodore Roszak, who coined the term “counterculture,” writes in his book The Making of a Counterculture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition “We grasp the underlying unity of the counter cultural variety, then, if we see beat-hip bohemianism as an effort to work out the personality structure and total life style that follow from New Left social criticism. At their best, these young bohemians are the would-be utopian pioneers of the world that lies beyond intellectual rejection of the Great Society” (66). The cultural bohemians who become known as hippies spring from a time of idealism where a wide array of lifestyles were created to attempt a physical and personal expression of utopian views spawned by New Left thinkers. This then is my working definition of Counterculture.

Years later, in a 2004 postscript to the 1981 book The Survival of a Counterculture: Ideological Work and Everyday Life Among Rural Communards, Bennet M. Berger writes “Citing a distinction between ‘cultural’ and ‘political’ rebels is not entirely adequate, in part because some Hippies had New Left sympathies and participated in their protest actions, and some partisans of the New Left looked and acted like Hippies when they were not on the barricades or marching in protest” (xii). Though he later reflects, “their fundamental differences eventually split them apart” (xii).

The various factions appear to be more alike than current accepted definitions claim, once one begins to examine the patterns of childhood experience and later life choices expressed by adult Post-Cool Kids. The effects of these experimental lives of this larger counterculture group including New Left, Hippie, and New Religions, on their children justifies the original expanded definition of what constitutes the 1960s counterculture.

When choosing subjects for the Family Lifestyles Project (FLS), a 20-year longitudinal study of countercultural families begun at UCLA in 1974, counterculture attributes were not defined before subject selection, instead an open call went out to places where people in the counterculture would be likely to see it. The subjects for the study—consisting of alternative California families, in which the mother was in her third trimester of pregnancy in 1974—self-selected into the study. The counterculture values were defined once the sample had been selected and interviewed. These counterculture families included a wide spectrum that matches more closely Roszak’s original conception than the now simplified definition of counterculture as simply hippies. In his article from this study “The American Dependency Conflict: Continuities and Discontinuities in Behavior and Values of Counter-Cultural Parents and Their Children,” Thomas S. Weisner writes “There were many sub-groups making up the counterculture with often conflicting ideas, and so no person or community believed in all parts of this sometimes contradictory agenda for change” (9). The sample included so many variants of alternative lifestyle and belief that FLS organized their subjects along family grouping types that defined parental circumstances and commitment to counterculture. These groupings were labeled, Communal, Avant-Garde, Countercultural, Conventional Alternative, Changeable/Troubled and the comparison sample of Conventionally Married. The study defined counterculture as a commitment to a set of “eight values orientations which both characterized the countercultural movements and mattered to parents” (10). These values included, alternative achievement goals, pro-naturalism (environmental concerns, emotional openness, being “laid-back”), gender egalitarianism, humanism, a present rather than future orientation, an acceptance of non-conventional authority and distrust of conventional social authorities, relatively low interest in a scientific/rational approach to life, and anti-materialism.

In 1976 John Rothchild and Susan Wolf published a book The Children of the Counterculture: How the Life-style of America’s Flower Children Has Affected an Even Younger Generation that described their journey across the country visiting intentional communities. They also initially echo this expanded definition of counterculture as defined by Roszak, choosing to visit all of the children of these various subgroups, New Left, New Religions, and Hippies, in their journey. Their conclusion is that only the hippie communes hold an authenticity that can be labeled truly counterculture. They write, “If there can be a new child only to the degree that there is a new parent, then we wanted to meet people who were raising their unconscious, who were fighting the invisible mother and the deeper American instincts that had survived the Red Family and its revolution” (52). Their bias of authenticity could be linked to their own self-critical preoccupation with legitimacy. Throughout the book, they compare their own children to the many counterculture children they observe. They describe their children as typical whiny American kids when compared with the rural commune kids. Yet their own children are allowed to smoke marijuana at the age of four and six, are living in a van with their parents, and traveling around the country visiting communes and experimental communities. One wonders what these young humans might say now about that experience. My hypothesis is that the hang ups and authenticities developed in the commune children would also now be present in Rothchild and Wolf's adult children who experienced both the journey to all of these places, the bonding with all of these children, and the cultural critique brought down on them by their own parents' responses.

Later writings have echoed Rothchild and Wolf in proclaiming an ideological split between hippies, left and new religions that was too broad to reconcile Roszak’s original stance that the counterculture were people creating lifestyles purposely actualizing new left values. The splitting of these groups led to analysis that limited the potential to see that all of the children in these groups, as individuals, were experiencing alternative lifestyles that later confirmed them as permanent outsiders to the “straight” world in similar ways. While in the short-sighted view of 1976 only the most extreme cases of children in rural communes could be seen to have a true counterculture experience, now that the children are adults a much larger body of people can be defined as significantly different from the “norm” and connected to each other by the experiments of the 1960s. The UCLA Family Lifestyles Project describes in various papers an ability in counterculture children to be successful in the conventional requirements of society, achievement in school, normative levels of mental health, and an understanding of individual attachment yet, in “Children of the 1960s at Midlife: Generational Identity and the Family Adaptive Project,” Thomas S. Weisner and Lucinda P. Bernheimer write of the studies findings that in the mid 1990s the young adult children of the counterculture continued to hold the values of their parents. The initial values of the counterculture as defined by the Family Lifestyles Project listed earlier, alternative achievement goals, pro-naturalism, humanism, a present rather than future orientation, an acceptance of non-conventional authority, gender egalitarianism, low interest in scientific and rational understanding, and anti-materialism. In a survey given to the children who participated in the Family Lifestyles Project when they were of college age these teens were found to be “substantially more left of the political center than the national Astin sample” (244) the questionnaire that is given to incoming students to measure the values and attitudes of American College Freshman.

Some of the lifestyle choices valued by this larger counterculture group come from a longing for authentic life experience. In his book The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure Victor Turner describes a type of group experience called communitas, interacting as equals in an energized, emotionally merged relationship. Counterculture children were taught that the attributes of communitas were desirable: equality, anonymity, absence of property, nakedness, absence of rank, personal relatedness, sacredness, simplicity, foolishness, unselfishness, and spontaneity, to give a partial list. They were encouraged to be authentic at all times. As a result their personas, the layer of the personality that acts as a socialized veil between the outside world and the individual ego, was often underdeveloped to the point of seeming nonexistance. As children they were supported in expressing exactly what they thought when they thought it. This authentic stance, which for the adults is a repositioning and stripping away of conventional “straight world” experience, was for the children developed from birth. The overt communication to these children was to hide nothing. All thoughts and feelings were laid out before the larger community. This encouragement of authenticity in children had two effects: first an obvious culture-clash with the mainstream world who did not expect a child to say everything they were thinking, and second a subtle stashing of true feelings in order to keep some level of privacy.

The communitas of the counterculture developed elements of coded communication as a way of recognizing the completely unorganized members of the group. Barbara Meyerhoff, who was a sociologist at UCLA, wrote an article “Organization and Ecstasy: Deliberate and Accidental Communitas Among Huichol Indians and American Youth," In her article she describes the way Turner’s concept of communitas plays out within the population she initially describes as "Woodstock Pilgrims." She sees the affects of communitas as a form of posturing, to show belonging within the culture. The need for posturing comes out of a need to be recognized by others as belonging to the group, and can be attributed to a lack of central belief or shared location that would traditionally define belonging. This coded cultural belonging is an attribute of popular culture notions of cool. Looking at the history of American Cool originating in African American cool culture, traditions and postures of cool within the counterculture can be identified and dissected. Understanding how cool culture codes counterculture ways of communicating provides insight into unspoken and sometimes unconscious conceptions of insider that subtly inform the experience of identity for Post-Cool Kids. The origins and developments of Cool historically link African American culture, music and aesthetics to the larger American understandings of what it is to be cool, and the postures of being cool, including drug use, creativity and psychological defense mechanisms infuse counterculture first intentionally by the parent group, and then as inherited understanding for their children.

Erik Erikson writes extensively on the connection between early socialization and ego development. He identified ways in which choices in child rearing impact the way a particular group experiences the world, and how this socialization through ego development, feeds into the choices and talents of the individual children that later bolster the original structures of the society. Children raised in a state of communitas develop a unique set of ego traits that include a longing for authentic connection. There is no place on the map where counterculture people come from, the group shares an array of possible connections and experiences, but is not easily identifiable or tied to place, as a result an unusual issue of feeling like an outsider occurs for the members of this scattered, disorganized, postmodern tribe. At the same time they experience an interesting set of psychological tools that values self-driven, passion-based projects and encourages the experience of flow or optimal experience, defined as autotelic activity by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Optimal experience helps develop a complexity of thinking and a focus. This state of experiencing was often over-valued within counterculture families and communities. It was cultivated and celebrated when displayed by counterculture children. As an attribute of their socializing it provides Post-Cool Kids with a greater propensity for success in creative, self-motivated, work.

During the 1980s many of the counterculture families experienced a return to the dominant society. This coincided with the Post-Cool Kid’s preteen or early teen years. In memoirs by both parents and children of counterculture families this transition is described, often expressing the disruptive bitter and confusing transition from a counterculture lifestyle back into the mainstream. In some cases small groups managed to remain outside of society longer, and some still reside in pockets of rural or specialized spaces. Bennet M. Berger, a sociologist studying communes in Mendocino, California developing through the sixties and seventies, wrote an updated prologue in the nineteen nineties looking back on the results of his study. In the case of communities that remained intact even into the late eighties, the children raised in these communities still entered the mainstream but not until they were young adults. The reasons for the return to the larger world were often economic and logistic rather than a change in values. The “return” of the parents was in most cases the initial entry for the children. Complex issues of authority within the larger conventional culture of the United States confronted the counterculture children as their parents returned to the mainstream social systems they had rejected. Their parents had raised them within a cultural dynamic specifically designed in opposition to the dominant cultural paradigms of the United States in the fifties and sixties. Among other aspects the ways authority was questioned in the counterculture ran counter to dominant expectations. The awareness of this antoganism, though mythologised within counterculture homes, was often not experienced by counterculture children until they began public school, or until they were first immersed in a larger junior high or high school. Many Post-Cool Kids report struggling and often never fully grasping the patterns of authority.

Much academic, depth psychological, theological, and even self help writing, stands on the assumption that since the enlightenment there has been a steady progression towards a complete mind and body split, and that western culture is in need of a more embodied, experiential, and as Nietzsche proclaimed in The Birth of Tragedy, “Dionysian” way of being, to counter balance the current ossification of the society. This call can be found as a primary theme in a wide range of current thought. Counterculture children however did not experience this lack of Dionysian energy in their upbringing. Dionysus was already unleashed in their world and running through the hills with the madness of his Maenads. Without a ritual container he has run freely and in abundance as a subliminal Other to the mainstream culture. The counterculture values pleasure and often cultivates experiences designed to activate Dionysian energy. Individuals raised in the excesses of a counterculture entranced with intense experience do not suffer from lack of embodiment. They are in need of the container. In the original Dionysian Festival of Athens the ritual required a sense of containment, the time and space of the theater, to create context and make sense of the excess. Uncontained ecstatic ritual has no way of stopping, or forming into a coherence. As teenagers and young adults, trying to understand the mainstream, counterculture children had a difficult time relating to the mind/body split of dominant culture. Post-Cool Kids often manifest issues of discomfort and alienation from mainstream mental health, spiritual development, or self improvement environments as they do not speak to the struggles they experience. A call for Dionysus as the wild, natural, excess, as something lacking doesn't resonate and is in opposition to the experience of Post-Cool Kids. Their relationship to mind and body, naturalness, and experiential excess is clear. Post-Cool Kids seek help with the flooding of experience and feelings of distortion, timelessness, or unstructured enmeshment.

Post-Cool Kids have up until now been an invisible group lumped in with the more identifiable Generation X. While many of their attributes coincide with descriptions of Generation X, there are important distinctions. The similarities and differences between mainstream GenX and Post-Cool counterculture children was already manifest during their teen years. There is a contrast between the nihilism of Generation X and the still hopeful, but guarded, utopianism of Post-Cool Kids. What is notable is that many of the overt portrayals of counterculture teen perspectives from the 80s and early 90s while resonant for the larger GenX population, are actualy depictions of the smaller Post-Cool subgroup. Even some of the icons of Gen X popular culture such as the movies Valley Girl and Repo Man describe counterculture children and not conventional suburban Gen X teens, their character transformations occur as a result of counterculture valuations.

David C. Pollock and Ruth E. Van Reken set a precedent for describing a type of post modern culture that they call Third Culture Kids where the culture is a “created, shared, and learned” (16) lifestyle that a group of disconnected people of different races, cultures, creeds and ethnicities all share. They write, “if culture in its broadest sense is a way of life shared with other, there’s no question that, in spite of their differences, TCKs of all stripes and persuasions from countless countries share remarkably important and similar life experiences through the very process of living in, and among, different cultures” (16). Not only is this description of a shared culture as lifestyle, outside of specific location and daily ritual, useful to the identification of Post-Cool Kids, but TCKs and Post-Cool Kids also share some of the same behaviors and psychologies. A major difference however is that Third Culture Kids live under the pressure of Modernist values that include keeping up appearances for the sake of their parents’ jobs, while Post-Cool Kids are taught to question external rules no matter where they land.

Mainstream roles of parent and child, the relationship to material goods, and the Post-Cool teen’s avenues for rebellion do not match the mainstream assumptions and expectations. The dominant culture psychological archetypes within the parent and child dynamic echo what James Hillman describes as the Senex and the Puer. The Senex best symbolized by the Saturnian influence of the grumpy old man is specifically counterposed against the Puer who is a youthful Peter Pan type character. Mainstream normative parenting leverages these archetypal modes with parents asserting authority over their playful and irresponsible children. Countercultural concepts of parenting abhor and at times demonize this picture of playful child and rule making adult. To the counterculture parent the entire story is a senex fantasy. Counterculture adults created a puer informed world, acting as permanent adolescents amongst the modernist, senex-like mainstream. For counterculture children their primary figures of authority, their parents, were proponents of anti-authority, and as a result conceptions of authority and hierarchy present as puzzles.

As the Counterculture children became Post-Cool young adults and were faced with mainstream expectations of success, identity, and lifestyle choices, many faced confusion and early crisis. How do you choose to become something when there are no expectations about what to become? What sort of rituals do you use to mark milestones in your life when all ritual is open to you? What constitutes individuation when you are simultaneously "on your own" and in a constant state of collective fusion? With a contradictory mix of adult experience, but child-like puer models of adulthood, Post-Cool young adults often went through a sort of early midlife crisis. They wrestled with the process of growing up, living between emotional struggle and personal acceptance. Trying to make meaning out of an unstructured and often trauma inducing past. Hyper aware of their bodies, as the result of a cultural insistence on intense sensory experience, they often develop trauma responses and psychosomatic sensitivity.

The result of living in this place of No Culture, New Culture, Multi-Culture is a complex array of postmodern ways of being. Ways that our parents, the people who “created” the 1960s counterculture could not themselves mimic, or even predict. This Second Generation, now as adults, sees the world with very different eyes from the “straight” culture, from their parents, their age peers, or even those people entering the counterculture today as first generation.

This is a description of a postmodern way of being that is more liminal than the postmodernism of the academy sometimes called “High-Modernism.” Academic post-modernism is in essence the culmination of modernism. The relationship to ideologies of modernism in that paradigm become deconstructed and pulled into a bricolage of parts. Academic postmodernism assumes a response to linear modernist narrative. Post-Cool Kids have always lived in a deconstructed and multi-storied world: early multicultural experiences; negotiating the counterculture and then the conventional world; absence of a named visible tribe; inventing their future when no future was defined for them; all inform their self-created identities. In an article from the UCLA study “Nonconventional Family Life-Styles and Sex Typing in Six-Year-Olds” Thomas Weisner uses the term “multi-schematic” to describe this multiple narrative way of being in the world. Rather than the holding one schema for how the world works, Post-Cool people are conscious of multiple simultaneous schemas existent in their world. They are adapted to witnessing these schemas, leveraging them to fit in with different audiences. In the sex typing study, which examined gender behavior in six-year-olds, counterculture children were seen switching between schemas to communicate with different audiences, already at that young age. Postmodern critical theory hints at the potential for a multi-schematic worldview but does not facilitate understanding of what this would look like as easily as does a conversation with a Post-Cool Kid.

The “loss” of myth regularly discussed in everything from academic texts to popular media is very different from the Post-Cool liminal experience of being raised with a more fluid, experimental story. As cultures begin to layer or fall away because of global movement and information technology, ideas of what is "normal" and "valued" has been shifting. Many studies relating to this speak of risk, confusion, loss. Within the counterculture this has already been true for over 50 years. Unlike those raised in a dominant cultural myth, people raised to believe that all myths are valid find it difficult to think in purely dialectic ways. Defining human experience becomes an exploration of personal understandings of truth, created narrative, body experience, and memory, in contradiction to any traditional text. As the multischematic psyche attempts to find meaning, rather than look for an ultimate signifier, a single god or belief, metaphors of experience become primary. Open-ended lists of possible explanations replace specific truth. By decentering the psyche and discussing various cultural complexes such as the various attributes and implications of Cool, or Questioning Authority, as unique entities within the individual—each working for their own agenda—one can shed light on how the postmodern psyche experiences meaning.

Post-Cool Kids express their values in everyday action. As a group they were raised on a high dose of utopian ideals. Their own lives are infused with intention. Regardless of individual values held, or actions taken, the act of intention is always present. They continue to redefine the cultural areas that their parents first questioned. Including their relationship to the environment, gender, the way they choose their partners, and community, the way that they choose to work, the things they eat, and the way they raise their own children. If asked, one will find that their choices are intentional, and resonant with socio-political meaning. The transformation of utopian experience in counterculture children from a universalist experimental practice, to a pragmatic activism, logically follows previous reports of utopian societies.

Post-Cool Kids often no longer consider themselves to be counterculture, and critique the extremes of their childhood vehemently. Yet, they hold many of the core values transmitted to them in their early childhood. They have taken these values and transformed them into cultural actions and artifacts. All informed by their pragmatic generational character, with a view to functional synthesis within the larger conventional society.

A study of this loose tribe I am calling Post-Cool Kids, is an attempt to process memory, to make sense of what was in many ways an initiation rite. Initiation that has permanently marked so many individuals who cannot recognize each other on sight, and yet are connected to each other through experience. This is a look at what worked, and what did not work in the experiment. The experimental act of trying to be authentic, unique, special, imaginative, in the face of the mechanical, titanic, military run, dominant Technocracy.

This work is meant to be a reality check for those who would do it again, “for the first time.” It is a push back to the critic who would pack away the sixties as a failed experiment. It is a handbook for the few who want to learn from our experiences. It is also a survival guide for the Post-Cool Kids still trying to define themselves, survive where they have been, and find some sort of connection to where they are now. The deconstructed, experimental, condition of the children of the counterculture was a deliberate act on the part of our parents. However, in its application it was unpredictable, messy, and the results are not fully digested.

Holding up this handful of unique lives to the light—in contrast to the titanic dominant culture—the various social critiques, and the romantic fantasies of the counterculture itself, changes the story that is The Sixties and brings the conversation forward into current history. It reframes the 1960s values not as an object fixed in amber, but as a cultural inheritance, and an ontological ordering of the world, that has been transmitted to the next generation.