Intensity Complex: Woodstock

Section 32 of my book: Transmissions From Parents to Children Within The Counterculture

Woodstock

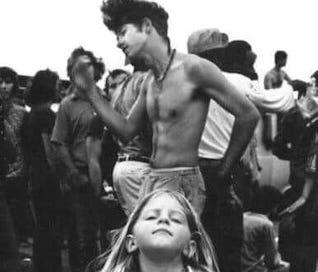

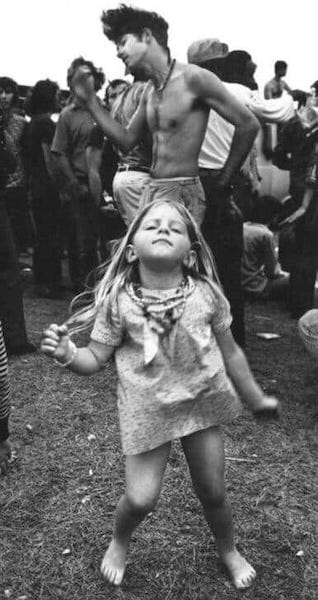

Looking specifically to the largest and most symbolically significant cultural happening of the 1960s counterculture, Woodstock, one can find the elements of the larger Dionysian ritual that was taking place throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Just as every American of a certain age can tell you what they were doing when Kennedy was shot, every counterculture American can tell you where they were during Woodstock, and every American Post-Cool Kid can tell you where their parents were. The impact of this focused event, though certainly not in reality the transformation of American society, mythically cannot be overestimated.

Nietzsche measures the Dionysian in an individual by their ability to feel, and especially to feel aesthetically. For him “the Dionysiac, with the primal pleasure it perceives even in pain, is the common womb from which both music and the tragic are born” (114). He measures the Dionysian in a cultural group by the strength of their myth and the power of their music, claiming that in these mediums we perceive Dionysus as “the playful construction and demolition of the world of individuality as an outpouring of primal pleasure and delight” (114). For the counterculture Woodstock was the realized symbolic representation of the living ritual, a perfected illustration of all of the mythic elements embodied in one giant spectacle.

Alice Echols writing about the transforming music scene in the Sixties suggests Woodstock is a mythic symbol rather than a concretely magic event that somehow created paradise on earth. “In the era’s lore, Woodstock has become synonymous with the ‘good sixties,’ with the beautiful people of the counterculture, while Altamont, the Rolling Stone’s free concert just four months later, has come to stand for the decade’s underside and the end of all that was hopeful in the hippie subculture” (46). She then rejects this dialectic by analyzing the difference between the belief that Woodstock was the height of unification for the culture. Contrasting it with the reality of Woodstock as the beginning of big concert events, and commercialism. Seeing this concert as the leap into a structure and hierarchy of these now highly profitable events that began to separate the bands from the audience. Diminishing the cultural feedback of close proximity that had developed in the San Francisco music scene.

There are many artifacts from the 1969 music festival that provide windows into the transformative energy that infused the ritual of the American 1960s. Joni Mitchell’s song “Woodstock” coalesced the event into symbolic imagery and became an inextricable link to the myth, which has developed around the event. In just a few short stanzas, Mitchell was able to create an epic-like narrative that not only describes the 1960s generation’s feelings of Woodstock, but also transforms the mundane event of a rock concert into a mythic tale. This song myth points to the underlying Dionysian energy that Woodstock specifically, and the counterculture revolution more generally, represented to the larger culture.

For the external world it would appear that Woodstock was in and of itself a ritual but for the counterculture it was the ideal moment in which the larger ritual reached an apogee of behavior. Illustrating what the desired constant must be. Not a moment in time with boundaried beginning and end, but a heightened moment in continuous time to be sustained now that the ideal had been identified. It is interesting to note that Joni Mitchell did not go to Woodstock. The poem was written while she sat in her apartment watching the news reports about the concert, having been talked out of going. Mitchell used Woodstock to express a feeling, a metaphorical representation of an ideal that already existed in the daily experience of the counterculture. The mythic nature of the song’s words come from this symbolic understanding of the ritualized communitas that the music festival engendered. Woodstock was the ideal embodiment of a ritual energy that was occurring across the country. Writing on the effects of Dionysian energy Edward Edinger states, “Dionysus and what he signifies promotes a sense of communion with humanity and a dissolution of differences” (153). Woodstock was the 1960s Dionysian dissolution fully realized. Paul Lyons writes of the cultural impact of this communitas,

The neobohemians, the hippies and freaks, would provoke the culture toward greater tolerance for difference and greater capacity for human pleasure. They would also force all of us to pay more attention to the ways we treated our bodies and the earth itself. It was not a marginal contribution to help Americans see that knowledge without wisdom, work without play, sex without pleasure, religion without spirituality were unsatisfactory. (71)

The powerful coupling of ideals with pleasure reverberates throughout the mythologies constructed around Woodstock.

Mitchell’s song invokes all the symbols that hold numin (magical energy) either negative or positive for the counterculture, proclaiming the music festival to be a perfect coming together of the larger rituals elements. The song canonizes these mythic elements by folding them into this quintessential event. In his book The Making of a Counterculture, Theodore Roszak describes the societal values of the counterculture in which, “the primary purpose of human existence is not to devise ways of piling up ever greater heaps of knowledge, but to discover ways to live from day to day that integrate the whole of our nature by way of yielding nobility of conduct, honest fellowship, and joy” (233). These values are echoed in Mitchell’s poem through counterculture norms of communitas, naturalism, and anti-war sentiment.

In The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage Todd Gitlin writes,

“Woodstock, in August, had been the long-deferred Festival of Life. So said not only Time and Newsweek but world-weary friends who had navigated the traffic-blocked thruway and felt the new society aborning, half a million strong, stoned and happy on that muddy farm . . . that possible and impending good society the vision of which would keep politicos honest” (406).

The images presented in Mitchell’s poem utilize a cosmological structure that, through the consensus of popular culture, becomes the agreed description of the event. A few lines create the commonly held picture of Woodstock: the location “Yasgur’s farm,” the intention to “get my soul free,” the reasons both to “lose the smog” and because “I feel to be a cog,” and the scale “half a million strong.” These facts, stripped down to near abstraction, become symbolic representations of a larger worldview that are the ideals of the “Woodstock Nation”. These images have been recycled for every modern depiction of Woodstock that wishes to utilize the myth of the concert as a symbolic representation of an ideal.

A naturalism and anti-technocratic simplicity is proclaimed in Mitchell’s lines “he was walking along the road” and “camp out on the land,” suggestive of the emphasis on a return to nature that later fed the exodus to rural and communal living in the early 1970s. David Farber, in his book The Age Of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s, describes how many of the counterculture decided to “move on from the glory days of the counterculture to other experiments in community building” (187). By 1971 the Whole Earth Catalog which “provided a wealth of information on how to set up a rural commune or homestead” was “a national best-seller, entrancing hundreds of thousands of people who fantasized what it would be like if . . . .” (Farber 188). Farber’s “if” could be easily completed with: we “get ourselves back to the garden.”

Mitchell’s line “the bombers riding shotgun in the sky” expresses the ominous feelings of war that were constantly overhead, in the minds of military aged young people confronting a universal draft completely influenced by the Vietnam War experience. Douglas Brode in his book From Walt to Woodstock: How Disney Created the Counterculture describes the connection between the rock concert and the war.

Woodstock’s three days of peace, love, and music, appears far removed from anything so dark as death. In fact, every element of the youth culture existed as a reaction to the ultimate event in all our lives. For essential to the 1960s social revolution was the Vietnam War: Hippiedom coalesced as a result of collective horror at daily body counts in a faraway land. (176)

Mitchell’s allusion to the bombers echoes this claim. Woodstock becomes the place where warplanes turn to “butterflies above our nation.” Butterflies are symbolic of the soul, and rebirth, and are often associated specifically with the souls of children. “Above our nation” calls up images of flag waving, and ‘nations under god,’ creating a powerful political statement in which the youthful souls of Woodstock become the new political power transforming the warplanes into images of soulfulness.

Woodstock has been canonized in the history of 1960s American culture as the quintessential transformational moment of the decade. It is used to mark time, as a turning point—rightly or wrongly—between the innocence of the youth culture, and the extreme militancy, drug abuse, and fragmentation that followed in the early 1970s. Barbara Myerhoff in her article “Organization and Ecstasy: Deliberate and Accidental Communitas among Huichol Indians and American Youth” writes, “Woodstock became a kind of lost paradise, haunting and elusive to its devotees, both for those who had actually been there and for those who knew it vicariously and mythically” (37).

The image of bombers turning into “butterflies” symbolic of the rising up of the child-like souls of the new “Woodstock Nation” with their most important ideal “we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden” clasped tightly to their breasts invokes utopian fantasies of paradise. The “garden” as Mario Jacoby writes in Longing For Paradise: Psychological Perspectives on an Archetype, is “a longing to be cradled in a conflict-free unitary reality, which takes on symbolic form in the image of Paradise” (9). The mystical elements presented in the song Woodstock are founded in concepts of purity, counterbalanced against evil. In the chorus Mitchell defines humans as “stardust” and “golden,” to connect us with the universal materials of goodness. Stardust evokes both a literal scientific unity with universal matter, in that we are made up of “billion year old carbon,” but it also implies an ethereal beauty, a link to the skies, to heaven and the gods. Gold is the material of solar goodness, linked to purity, immortality and knowledge.

Yet, we are “caught in the devil’s bargain.” The devil is known as the great divider and tempter towards evil. The wish for Paradise was amplified for the counterculture by Timothy Leary’s insistence that ego death was the necessary path that the youth culture should take towards awakening, “The LSD doctor spoke of a chemical doorway through which one could leave the ‘fake prop-television-set America’ and enter the equivalent of the Garden of Eden, a realm of unprogrammed beginnings where there was no distinction between matter and spirit, no individual personality to bear the brunt of life’s flickering sadness” (Lee and Schlain 183).

Jacoby discusses two psychological motivations for a longing to return to Paradise, either a regressive wish for the uroboric merging of mother and infant, or an advanced stage of Jungian individuation in which “an intensive encounter with the inner world and its center, the self,” generates “an experience of the most intense numinosity” (207). This encounter creates a feeling of personal connectedness and a sense that the universe holds a magical awe that makes life worth living. Mitchell’s song suggests that the energy found at Woodstock is the key to a mythical Edenic time. This Eden is a naked, LSD riddled, rock concert sort of Paradise, where Dionysus the god of wild natural libido reigns, and purification comes from a dunking into the mud. The myth of Woodstock as paradise reverberates throughout the rest of the counterculture and the ritual of American transformation, pointing to the idealized version of unification and intensity.